I’ve done it in the grocery store in the applesauce aisle. I’ve also done it while walking down 17th Street, NW and on the Metro platform at Farragut North.

What have I done?

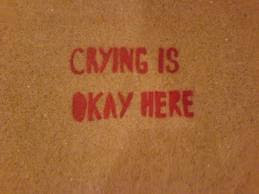

Crying in public. And you know what?

When I was doing it, I could have cared less about who I ran into or what I looked like. I was in the throes of grief and I had either heard a song that reminded me of my husband or was coming from a situation where no one acknowledged my loss or what was happening to me.

When I was doing it, I felt as if I was in a bubble; a bubble of trouble, and I had no expectations that anyone would come up to me and put their arms around me or try to comfort me.

I did it because I wanted to; plain and simple and it made me feel better. I was not trying to draw attention to myself. I was just trying to put myself back together and crying was liberating.After reading the story below, I know that I’m not alone. And if you find yourself crying in public, don’t feel ashamed.

Look at Me, I’m Crying

By MELISSA FEBOSApril 20, 2011

The New York Times

I’ve done it on the subway and at the Museum of Modern Art, in Prospect Park, Tompkins Square Park and leaning against the locked gate of Gramercy Park.

If you live in New York, you’re bound to end up crying in public eventually; there just aren’t enough private places. Just the other day I saw someone doing it on West 12th Street. A tall woman in a beret, with a curtain of reddish hair, she had tears streaming down her cheeks. She wasn’t on the phone, wasn’t accompanied by a man, or a mom or even a dog. She wasn’t beautiful, the way a lot of people in New York are, but I couldn’t look away.

My stride didn’t change as we passed each other, but something did. A fizzy kind of sweetness bubbled up — as if the openness of her face had opened something in me. For a few minutes I forgot whatever I’d been worrying about and breathed a little deeper.

The redhead was a particular type of public weeper: silent, dignified, angelic. I hope that when it happens to me, it looks like that, though I suspect there is more whimper, more grimace.

But even the unpretty ones, snuffling, their faces like balled napkins, are mesmerizing. There is something beautiful about a disarmed stranger. We usually only get to witness that kind of vulnerability with friends or family, when something — sympathy or apology — is expected of us. Public criers ask nothing; they don’t need anyone to take care of them.

In some ways, that kind of transparency is as good a defense against interference as the famous blank New York stare.

Public criers ask nothing; they don’t need anyone to take care of them.

One afternoon, I was riding a Brooklyn-bound Q train with my mother, who was visiting from Cape Cod, when our conversation lulled. We each glanced around the subway car at the other passengers, their heads bobbing in unison, the eyes of the man across from us doing a creepy back-and-forth twitch as he watched a train whizzing by in the opposite direction behind us. Some people read, or pushed buttons on their smart phones, but most just stared without expression at the floor or the garish overhead posters for Dr. Zizmor’s cosmetic dermatology. My mother (who is, notably, a psychotherapist) leaned into my shoulder and whispered, “Everyone on this train looks depressed.”

I snorted, whispering back: “No, Mom, they just have their train-faces on.”

In a place where we are so rarely alone, we find privacy in public. We all have our masks, behind which we are free to be, yes, depressed, or any other emotional state we may not want to share with 30 fellow passengers.

The problem is, we often don’t want to show our emotions to our true intimates either. The apartment I share with my girlfriend is so small, it can be easier to find privacy outside. During a recent fight, we reached an impasse; we were clearly not going to reach a resolution. We rarely fight, but when we do, it feels like there isn’t enough room in our apartment for both of our feelings. And there’s nowhere to have a phone conversation that the other won’t overhear. So I went outside to walk the dog.

Through a number of domestic partnerships, walking the dog has been a form of privacy for me. I’ve made many of my most personal phone calls during those walks, cooled off and of course, had a good cry. It’s even easier to let loose in public when you’ve got a 70-pound pit-bull in tow, and when you’re on the move.

On that same visit, my mother commented on how fast people walk here. I had, at the moment she spoke, been furious at the tourists in front of us for strolling so lackadaisically, despite our not being in a hurry to get anywhere. I began with the usual explanation, about how busy everyone here is. But mid-sentence, I realized that that wasn’t the whole story; movement was part of the mask.

Although I see plenty of stony-faced striders on the sidewalks of New York, the faster people are moving, the more they tend to reveal. When riding my bike through the city, I frequently sing aloud — mostly old soul tunes, but everything from country to rap music — and I hear other bikers doing it as well. Because who cares? If anyone stares, they’re staring at your back and you’re not around long enough to notice. I don’t do it for attention; it just feels good to belt out “Tenderness” with impunity.

Perhaps this law of motion is part of why it’s so startling to see people trip. It’s bound to happen millions of times a day here, but still, seeing someone stumble instantly provokes a deep cringe. Like crying, it’s a glimpse of pure, involuntary vulnerability, and yet there’s something different about it; it’s more disturbing than sweet. We feel a greater demand to lend a hand or show concern because we know, more clearly, that it could happen to us — we like to think we have less control over our bodies than we do over our emotions. We all can feel the stumbler’s flush of embarrassment. So we grimace, surge with silent sympathy, and reach out.

Even though as any stumbler knows, the worst part, after detaching a heel from the subway grating, is someone asking “Are you O.K.?”

Of course some people feel differently. They want to be asked. They even want to be asked why they’re crying. Maybe people can be divided into those who want to be asked what’s wrong by kind strangers, and those who don’t.

For me, it’s not that I want apathy, just privacy. To be noticed, but not interrupted. It’s comforting to be seen in our grief, there is a confirmation in it — however awkward it makes us feel. Is that part of why we live here? New Yorkers do tend to be the kind of people with both a need to be seen, and a deep fear of it. Somehow, this place satisfies both.

When I first moved here, I loved to ride the elevated trains, especially at night, when I could glimpse the thousands of glowing windows, each an indication of a life or a cluster of lives, as rich and difficult and sweet as my own. Glimpsing inside, seeing the moment when the lights go on — or off — is a confirmation of our likenesses, our common depths.

I know I’m not the only one who feels that way, and hope I’m not the only one who sees something more uplifting than snot in the face of a public crier. Because just Monday morning, coming up from the subway at Eighth Street, it happened again.

My phone rang. “Hi, Mom,” I said. For many reasons, it had been a hard few weeks. The right voice at the right time, and the seal between my public face and the feelings underneath it broke.

“What’s wrong?” she asked, and behind my lenses, the city went soft. Soon, tears collected under my chin, and I lifted my glasses to wipe my eyes. The sun was bright, the sidewalk crowded, but I was still moving, and the city’s edges had all blurred to water, the passing faces turning to patches of color. Even if, at that moment, I had cared whether they were staring, I wouldn’t have been able to tell.

Melissa Febos, the author of the memoir “Whip Smart,” teaches writing at Sarah Lawrence, the New School and New York University.

Leave a Reply